Exposed: 4 Investing Myths Believed by Financial Advisors

The Truth About What Most Advisors Believe

Introduction

I read an article online recently discussing how much money you need in order to retire. According to the author, the figure is $1.2 million.

I hate those kinds of articles. They encourage the false belief that people need to hit some magic number for retirement, which is far from the truth. There are a lot of factors that matter: health, longevity, having a pension, investment returns, etc.

While the value of savings is certainly one of the most important factors, I’d argue that spending is an even bigger factor, and at least it is something that you have a degree of control over.

I’ve known plenty of retirees who have done just fine on far less than $1,000,000 of savings, say, $250,000-$400,000. The key was having their homes paid off and living within their means.

By the same token, we’ve fired clients worth millions whose spending habits were so out of control that there was no way their savings would last through retirement.

Anyway, the article got me thinking about common investing myths that financial advisors believe. I came up with four that are just plain wrong and oftentimes silly when you think about it.

Myth #1 – Because markets are impossible to predict, you should just invest in everything.

Proponents of this view tend to tout asset allocation and diversification as the be-all and end-all of investing. In reality, however, most portfolios have become over-diversified and sub-optimal on nearly every level thanks to the cult of asset allocation.

Let’s look at investing in international stocks as an example. Devotees of asset allocation often advocate owning all publicly traded stocks according to their respective weights in global indices, which ends up being roughly 55% U.S. stocks and 45% international stocks.

When pressed for why you need to own so many international stocks (Many large U.S. corporations already have a significant portion of revenues coming from overseas anyway.), you are told that predicting which stocks will outperform every year is impossible, so it’s best to own them all. They will also point out that international stocks outperformed U.S. stocks from 2000-2009, which might happen again.

This line of reasoning isn’t dumb, and I fully agree that we’ll see another period when international stocks outperform. Yet…

Did you know that if we zoom further out, the performance of U.S. stocks has left international stocks in the dust? Going back to 1986 when we start to have good data on international stocks, a $10,000 investment in U.S. stocks would be worth $363,000 today versus only $92,000 for international stocks. So, rather than benefitting investors, blindly owning international stocks at all times has actually hurt them.

What else do we know? Well…

• Every time there is a crisis or recession, international stocks perform materially worse than U.S. stocks.

• International stocks tend to outperform U.S. stocks during periods when the value of the US dollar is trending down.

• Strong economic growth often doesn’t translate into strong stock market returns, especially overseas. (Look at how poorly China’s stock market has performed compared to its economy.)

Given the three points above, it is obvious that there are periods when it makes more or less sense to invest in international stocks. And if you cared to dig deeper, you would find plenty of other facts that you could use to inform your decision about investing internationally.

What I am saying is that if you are getting paid to manage someone’s money, you have a duty to invest using a framework based on investing principles such as buying low and selling high, and risk versus reward, regardless of how difficult it is to predict the future.

Imagine for a second that you run a consumer goods business and you were looking to expand into different international markets. Before choosing where you’d like to expand, you would conduct an analysis that looked at a variety of factors, including political stability, the strength of institutions, ease of doing business, demographics, ROI, etc. Then you would make an investment decision based on your analysis.

What you wouldn’t do is invest in every single market in the world just because you can’t predict the future. Think about how crazy that would be. Yet, every day this is exactly what financial advisors are doing with their clients’ hard-earned savings when they tout “owning all the stocks.”

Myth #2 – Diversification is the only risk management strategy you need.

Now, I’m not saying that you should own just one stock, or that diversification is pointless. It’s obviously necessary to prevent you from losing all your money on one bad investment.

What I am saying is that it’s no substitute for risk management and that it is likely to fail exactly when you need it the most.

Let’s take the example of bonds as a diversifier. The main reason that most advisors invest in bonds is the belief that they tend to go up in value when stocks fall. This is true sometimes. But not always!

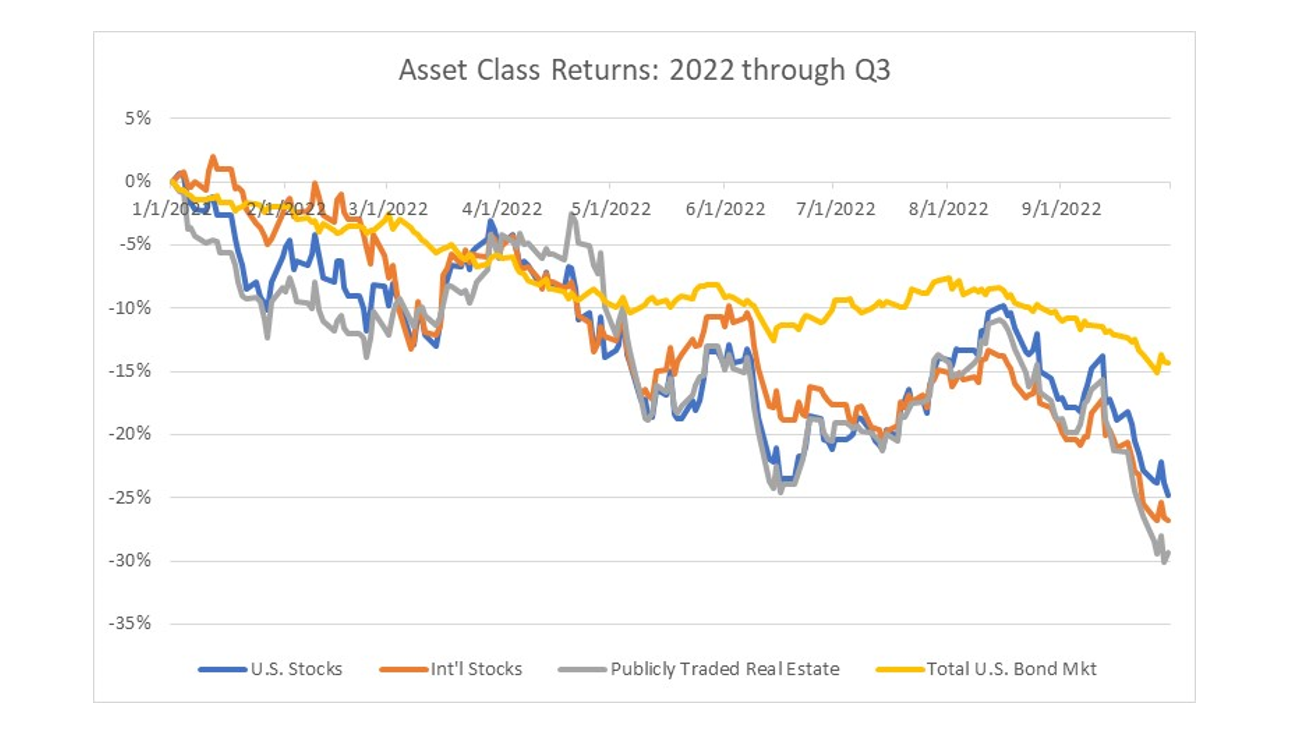

From January through September 2022, both stocks and bonds were down double digits. At one point during the year, the Vanguard Target Retirement Income Fund, a common investment for retirees, was down 16.5%, delivering quite a shock to conservative investors.

The chart below shows U.S. stocks, international stocks, publicly traded real estate, and bonds.

How helpful was diversification at reducing risk?

The reality is that relying on diversification as your sole means of risk mitigation is wholly inadequate. I might even call it cavalier.

Let’s return again to the example of running a business. If you ran a business and thought that we were headed for a major global recession, would you believe that having a presence in multiple global markets was adequate risk mitigation?

Would you throw your hands up and say, “Well, there’s nothing we can do, but at least we are diversified.”?

Of course not. At a minimum, you would stop hiring, consider reducing headcount, pause capital projects that weren’t absolutely necessary, and look to reduce expenses anywhere you could.

Why should investing be so different? It shouldn’t be, and everyone should have a risk management strategy in place beyond diversification.

Myth #3 – Time in the market, not timing the market.

Sure, timing the market is difficult. Lots of studies prove this, after all. Nevertheless, the advisors who endorse this saying do so by showing how being out of the market during the best X number of days in a year would produce mediocre long-term returns.

While this is obviously true, it’s stupid because it fails to account for the opposite: how beneficial it is to miss out on the largest market declines.

Avoiding massive losses is actually more beneficial than being in the market during the days with the highest returns because of how compounding works. For example, it would take a gain of 100% to make up for a loss of 50%.

Did it make sense to own Treasuries once the yield on the 10-year bond fell to .53% in 2020?

Well, I certainly didn’t think locking in a .53% annual return for 10 years, less than inflation, was a good deal, and I can tell you, we choose to get rid of all our Treasury bond investments.

Now is this market timing? You bet. But that’s what prudent investors do when circumstances change, and new information becomes available; they don’t sit on their hands while preaching platitudes.

Myth #4 – Portfolios can be optimized.

This is one of my favorites. Portfolio optimization stems from ideas put forth in the 1950s by a finance professor named Harry Markowitz who used math from physics to show that there was an “efficient frontier” and that an “optimal portfolio” existed along that frontier.

Unfortunately, using math from physics doesn’t work with investing. The math used in what’s known as mean-variance optimization is based on assumptions that aren’t valid in the world of investing. For example, optimization assumes that investment returns exist in a steady-state world that doesn’t change, i.e., the correlation coefficient between assets is constant, which is simply untrue. It also assumes that returns follow a bell-shaped distribution. They don’t.

Funny story. In graduate school, I asked one of my finance professors why we use optimization when it’s empirically invalid. His reply was that we use it because it is mathematically elegant. What a stupid reason. No wonder there’s so much mistrust of experts these days.

But back to optimization. Even if the assumptions going into it were valid, portfolios are never optimized anyway. Why? Because the advisors using optimizers override the program’s investment suggestions by placing subjective constraints on the output.

You see, in their purest form, optimizers nearly always suggest investing in just two or three asset classes.

Advisors worry that investing in 2-3 asset classes isn’t enough because of their obsession with diversification, so they go back and place constraints on the portfolio, forcing minimum amounts to be invested in multiple asset classes regardless of whether or not it’s actually “optimal”.

The truth is that portfolio optimization is nothing more than an attempt by finance professionals to make the investment process seem more scientific and rigorous than it actually is.

Conclusion

I have no doubt that most financial advisors have good intentions. Unfortunately, they’ve become victims of groupthink and fear of career risk. It’s much easier to be wrong when everyone else is, too.

Sadly, this has led to a world where advisors have come to eschew common sense, as well as the basic principles of investing. They’ve decided that smart investing means owning everything at any price and simply rebalancing periodically.

I have a very different view. To me, smart investing is not sitting on your hands and doing nothing, nor is it jumping in and out of markets willy-nilly based on your gut feeling.

Smart investing involves humility. It’s an admission that the future is uncertain and that just because things have worked out well in the past, they might not always.

Smart investing involves having a process in place to evaluate risk, reward, and value. It means shunning investments that don’t meet your criteria, the opposite of buying at any price.

Finally, smart investing involves having a risk management plan in place for dealing with uncertainty, not simply relying on diversification. As they say, “Hope isn’t a strategy.”

If you are worried that your portfolio is on autopilot, reach out to a representative at Fortress Capital Advisors for a complimentary review.

Important Information

Investment advisory services are offered through Fortress Capital Advisors LLC, a fee-only, fiduciary registered investment advisor. This communication is not to be directly or indirectly interpreted as a solicitation of investment advisory services.

The contents of this communication and any accompanying documents are confidential and for the sole use of the recipient. They are not to be copied, quoted, excerpted or distributed without express written permission of the firm. Any other use beyond its author’s intent, distribution or copying of the contents of this presentation is strictly prohibited. Nothing on this website is intended as legal, accounting, tax or investment advice, and is for informational purposes only.